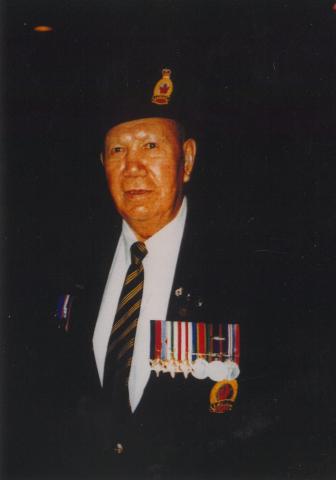

Remembering Métis Veteran Robert Berard

by Kirstan Schamuhn, Assistant Curator, Military and Government History

Métis Veteran Robert John Berard was born in Tofield, Alberta in 1921 and grew up with his five brothers and three sisters on a farm. The family moved to the Calder region where, according to an Edmonton Journal article from November 11, 1994, he “…dreamed of becoming one of the guys in uniform.” He trapped in northern Alberta, sold wood to the Hotel Macdonald, and trained with peacetime Canadian military forces to help provide for his family.

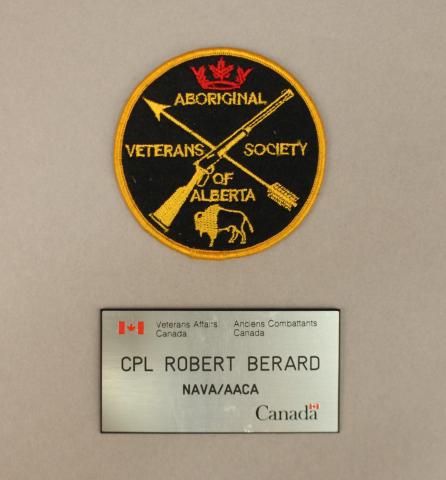

In 1941, Robert Berard enlisted in the Edmonton Fusiliers to serve in the Second World War. He was sent to Scotland in June 1942 as reinforcements for the Regina Rifles and was later transferred to the Royal Canadian Engineers. Robert Berard achieved the rank of Corporal, and served in Sicily, Italy, France, Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands.

During his service with the Royal Canadian Engineers, Berard disarmed and cleared enemy landmines, planted Canadian minefields, and built and repaired portable bridges for Allied forces. He was part of the Canadian and Allied forces that entered the Netherlands to liberate the country from German occupation. The Liberation of the Netherlands lasted from fall 1944 until German forces in the Netherlands surrendered on May 5, 1945.

Berard was interviewed by Veterans Affairs Canada about his experiences as an engineer in the Netherlands. When asked if his hunting and trapping experience helped him during his military service, he responded: “Oh yes lots, sleeping out at night and toughing it out. Walking all day that was, to me 20 miles to walk was nothing.”

After the war, Robert Berard returned to Edmonton and became an advocate for Indigenous Veterans. He was a member of the Aboriginal Veterans Society of Alberta and the National Aboriginal Veterans Association (now Aboriginal Veterans Autochtones). In 1995, Robert Berard travelled to the Netherlands for the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of the Netherlands ceremonies as a national representative for Aboriginal Veterans of Canada. Berard laid the wreath for Indigenous Veterans at the Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery.

In an interview with Veterans Affairs Canada, Berard shared his feelings about his time in the Canadian Army: “Army life was one of the best things that ever happened in my life because discipline is something I'll never forget. Even today if I met one of my friends, if he was broke I'd help him, cause I know he'd do the same for me and that's one reason I went back to Holland. To lay a wreath because I remember.”

It is unknown exactly how many Indigenous Veterans have served with Canadian military forces. Veterans Affairs Canada estimates over 12,000 Indigenous people, including Métis, Inuit, and First Nations (with and without legal status under the Indian Act) served in major conflicts in the 20th century.

For many Indigenous peoples, including those who joined the Canadian military and those who provided home-front aid, supporting Britain and Canada during wars was viewed as upholding alliances and treaty responsibilities. However, Indigenous Veterans often faced discrimination during their military service and upon returning home from war. The sacrifices Indigenous Veterans made for Canada during times of war were not recognized equally to non-Indigenous Veterans.

After the First World War, the Soldier Settlement Act (1919) granted returning Veterans land to homestead and farm. However, land administered under the Act was often expropriated (taken away) or surrendered from First Nations reserves to then be granted to largely non-Indigenous Veterans. Status First Nations Veterans could apply for land grants on or off reserve, however on-reserve land was still considered communally owned by the band, and leaving a reserve could require enfranchisement. Enfranchisement was a legal process which required status First Nations individuals to permanently give up their treaty and legal Indian statuses. In Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, treaty and non-treaty First Nations Veterans were entirely barred from receiving the grant because the Indian Act banned them from owning a homestead in those provinces. Additionally, upon returning to their reserves, status First Nations Veterans were excluded from receiving Veterans benefits under the Last Post Fund, Pensioners’ Relief, and Veterans Allowances. It took until 1936 and advocacy from the Royal Canadian Legion for the policy to be revised.

Following the Second World War, non-Indigenous Veterans were supported in securing land and equipment for farming under the Veterans’ Land Act (VLA). Veterans could purchase land through loans that came with reduced interest rates and approximately 39% of the loan amount was forgivable. Indigenous Veterans were heavily discriminated against from receiving these loans; status First Nations Veterans were only allowed to apply for a direct grant amounting to the forgivable portion of the VLA loan to support forestry, fishing, and farming projects. They could only purchase “occupational rights” to land on reserves. The Indian Affairs Branch (IAB) administered the grants by requiring that local Indian Agents had to recommend applications and an amount to be granted.

Métis Veterans also faced challenges in accessing the benefits that they were entitled to after their service. Many Métis Veterans were given the grant for status First Nations Veterans rather than the full amount of the VLA loan. Additionally, Indigenous Veterans were often not told that there were pensions, benefits, and grants that they could access when they returned home. Until 1985, under the Indian Act status First Nations peoples could not enter establishments that served alcohol, which included Canadian Legions. As a result, Indigenous Veterans were frequently turned away from Legions, which offered valuable resources, information, and support for applying to Veterans benefits. Further, many non-status Indigenous Veterans, such as Métis and Inuit Veterans, lived in remote communities without access to Legion branches or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Many Indigenous Veterans who returned to their home communities became vocal advocates and community leaders for change. Indigenous Veterans were instrumental in forming groups to support one another, and to advocate for Indigenous rights and better treatment of Indigenous peoples. Indigenous Veterans, like Robert Berard, fought for their service and sacrifices to be recognized by the Government of Canada.

For support or more information about Indigenous Veterans, please check out the following resources:

Hope for Wellness Helpline: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1576089519527/1576089566478

Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., Indigenous Veterans: https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/indigenous-veterans

Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples: https://data2.archives.ca/e/e448/e011188230-01.pdf

Veterans Affairs Canada, Indigenous Veterans: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/remembrance/people-and-stories/indigenous-veterans