A Well of History

Learning about Alberta’s early Black communities

By Mathew Levitt, Digital Media

Originally published February 6, 2018; Updated February 2021

I followed Paul Beaver up the path into the trees. It went deeper into the forest than I expected, but eventually we passed into a spacious glade. The grass was mowed and the brush was cut back but for the odd loitering evergreen, still standing where it had put down its roots all those years ago. While I wandered somewhat aimlessly, Paul surveyed the area with the same deliberate intent as someone who had dropped his keys. He then knelt down and waved me over.

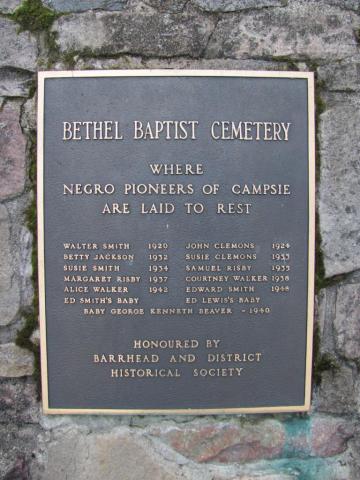

At first, I couldn’t see what he saw. Brushing away the leaves and deadfall, Paul showed me what was there: a grave marker. There are over a dozen such graves at the Bethel Baptist Cemetery, a somewhat hidden plot of land around 19 km west of Barrhead near the hamlet of Campsie. A stone cairn has kept vigil at the cemetery’s gates for half a century, reminding passersby that the hallowed spot is “where Negro Pioneers of Campsie are laid to rest.”

That day, after leaving the cemetery, Paul showed me around his ancestral homestead just down the road. Paul’s great grandparents, James Moses and Hattie Beaver, came to the area in 1910 and settled on the land where Paul and I now stood. The dilapidated two-storey house before us, surrounded by encroaching brush, was built in 1936 by Paul’s grandparents, Walker and Ivy Beaver. Now, it is one of Alberta’s nascent ruins: those ramshackle structures that dot the rural landscape and remind us that our province has grown up from painted timbers worn bare.

In the spring of 2016, I began working with descendants of Alberta’s early Black settlers to build the museum’s collection around their story. Working with descendants such as Paul has helped the museum to establish a much needed material record, which we used to create the I Am From Here exhibition, about Alberta’s early Black communities.

A historical photo of Paul beaver’s ancestral home, up the road from Campsie. His grandparents, Walker and Ivy Beaver, built the house in 1936.

Along with Campsie, the towns of Amber Valley, Keystone, and Wildwood (formerly Junkins) were settled by Black families. The settlers made their way up from the American South in the early 20th century. They were escaping the enflamed persecution they suffered under the Jim Crow laws, which enforced racial segregation. Black settlers made their homes in Calgary and Edmonton as well, establishing institutions that continue to thrive today, like the Shiloh Baptist Church, and others that no longer grace the cityscape, like Hattis Harlem Chicken Inn.

Paul stands in front of his grandparents’ two-storey house.

In the summer of 2016 I visited Keystone, about an hour’s drive southwest of Edmonton. The only way to get to old Keystone is to visit the Keystone Cemetery or the Breton and District Historical Museum. Like many other Alberta hometowns, Keystone is mostly a memory: stones on the ground, objects behind glass, and stories told. But whether or not these places still thrive, they live on for many who still remember them as home.

I have been both privileged and humbled to hear the stories, to hold the objects, and to meet the people who have grown from these towns down the road. One of the objects that Paul and his siblings have donated to the collection is an unassuming pulley wheel. When we first received the rusty wheel I wasn’t sure just what it had been used for or why it was important. But when I asked Paul about it he told me it was the pulley wheel from the well on his grandfather’s homestead. The well is gone now but the wheel remains to tell the story of those who dug it and drank from it; people who made a home on the land under which those waters ran.

I am continually reminded that our province’s heritage is a deep-dug well. All we need do is draw up the pail.